Reader, a confession: My mind drifts at times toward the academic and the abstract. It’s partly why I like doing client work—it keeps me grounded. But sometimes, the muscle memory of college years spent reading too much Nietzsche and Foucault comes back.

So I’ll find myself looking at an everyday topic and asking: What does this look like at a higher level of abstraction? Can we move upstream? Apply that principle back on itself?

That seems to be a common theme in a few of the articles I came across for this edition of the newsletter. Maybe that’s just where my head’s at right now. Or maybe that’s where many of us are: as Covid drags on—as even those of us in the US with the privilege of vaccine access stare down possible school closures (again) from the Delta variant. Time has stopped, time never was. We’re all caught in infinite recurrence.

So join me as we get so meta…

But first, a few updates on what I’ve been doing:

Facilitating, fast and slow - my latest on Medium: some reflections on how my work has evolved since the start of Covid. I’ve recently wrapped up a round of projects and have several in early planning, with the pace picking up in September. But one common theme: remote/virtual engagements will remain the norm.

I’ve also done a few podcast interviews recently. Usually as a strategy consultant I stay in the background, so it was great to talk about the ideas behind the work. Look for those in the coming weeks.

And finally, I’m writing a book. Working title: Together. More details soon.1

Programming note: Half the internet is behind a paywall these days, and a reader in Vietnam pointed out that they can’t even access Medium there. So if I ever link to anything that you can’t access for whatever reason, please feel free to ping me and I’ll get you the text.

Now on to the good stuff.

Telling a story about storytelling 📖

Changing Our Narrative about Narrative - In NPQ, Rashad Robinson shared a range of deeply insightful distinctions: between comms and narrative, between presence and power, between issue framing and brand narratives. This piece is actually a year old, but I just came across it and I can’t recommend it enough.

Systems Language for Narrative Power - Rinku Sen of the Narrative Initiative writes about making systems talk more accessible (and introduces the great framing of “people-centered systems analysis”) as a route to building narrative power. I liked this:

How we communicate about systems influences people’s ability to hold and use system-changing narratives. To change systems we need many people to hold and use shared stories about their ability, intention and vision to change systems.

Deep dive: “Measuring Narrative Change” 📐 - The story we tell about the role of narratives in social change often makes them feel fuzzy and abstract. Can we make them more concrete—even measurable—without forcing them to be something that they aren’t? This report from ORS Impact takes a step in that direction, with lots of definitions (differences between stories, narratives, meta-narratives, and elements of narrative), outlines of strategies (different types of change), and going all the way to the granular level (of outcomes and indicators).

Finally, a thread on models of narrative change:

Changing social change

There’s always interest in the power of movements and networks for change, but I was struck by two recent articles that took it up a level.

The Social Sector Needs a Meta Movement - from Laura Deaton of Multiplier, writing in SSIR.

Organizing Liberatory Networks: An Invitation - from Susan Misra, Trish Tchume, Robin Katcher, Natalie Bamdad, and Natasha Winegar of Change Elemental.

More broadly, the past year’s focus on racial justice has put renewed pressure on social change actors to think about how we do our work. SSIR ran a whole series on racism in organizations titled “This Is What Racism Looks Like”.

Accountability v Punishment - Piper Anderson (in that SSIR series) shares 7 practices for building a culture of accountability. I especially like this distinction:

The difference between accountability and punishment has to do with relationships. Punishment breaks a relationship; it’s rooted in isolation, shame, and disconnection. Accountability, by contrast, requires communication, negotiation of needs, the opportunity to repair harm, and the chance to prove that we can change and be worthy of trust again. Organizations committed to racial equity must recognize that this work requires new practices for talking about race and racism and new strategies for addressing acts of racial harm that seek repair and strengthen trust.

“Demand that the people with power be present” - That’s from the always-insightful Vu Le, writing on how power and privilege prevent change in our sector. The whole piece is worth reading, but that suggestion struck me. As a facilitator and consultant, how many times have I designed a process to help people make a decision, only to see someone fail to engage until the very end? It can look like delegating—which is good!—until they come in to disrupt the final decisions. In more toxic forms, they cast doubt on the whole process. 🤬

👥 Co-leadership: it takes two to make a thing go right?

It seems that more organizations are experimenting with co-leadership models, where two or more people share a leadership position equally. A few recent write-ups on different experiences:

Leadership Legacy - by Dana Kawaoka-Chen and Lorenzo Herrera y Lozano, co-directors of Justice Funders

Leadership Transitions - by Liz Derias and Shannon Ellis, co-directors of the leadership development organization CompassPoint

Co-leadership all the way down 🐢 - The co-CEOs and chief knowledge officer of the Jacobs Foundation write in Alliance Magazine about what they’ve learned in two years of instituting co-lead pairs for each key function in the organization.

HR and organizational development firm PTHR uses a three-person “leadership circle” along with team agreements and other mechanisms to create a leaderful culture.

(As always, read skeptically what anyone says about how they work internally. 🧐 )

Worker cooperatives: a different type of co-leadership? - Rebecca Bauen of the Democracy at Work Institute writes about what nonprofits can learn from worker cooperatives, sharing some great examples..

Bonus read on collaboration: a few management professors studied how people from different social/economic classes collaborate. The article has a few cringe moments as it describes class (after all, it’s the Harvard Business Review 💼 ) but here’s the key insight:

Groups from lower social-class backgrounds took more conversational turns while working together than groups from middle-class backgrounds, and had more active and balanced discussions, a crucial ingredient to high-performing teams. Indeed, our work suggests that people from lower social-class backgrounds are likely to bring unique, collaborative skills to organizations that help teams perform well.

… but how many to make it go wrong? ☠️

Since last summer, I’ve been adding to an open twitter thread on toxic leadership in the social sectors. The latest addition is The Appeal, a nonprofit newsroom focused on criminal justice that closed down a few months ago. I had only loosely followed the story until I saw this great piece on lessons, especially for donors, from what happened there. (Tl;dr - go beyond “investing in leaders”; build channels to the rank and file; encourage and support unions; and pay attention to the “dark side of metrics”.)

I’ll keep adding to the thread as more stories come up. Sadly, these are only the ones that make headlines. Many more examples permeate our sector, hobbling impact and harming staff.

Many of us (myself included) have worked in toxic environments, often papered over with the self-importance of the work and a sense of martyrdom. It’s hard to be in one of those cultures and not be a perpetrator and propagator of it too. We need a more systemic response than waiting for organizations to implode and then holding them up as cautionary tales.

A short break for a brain teaser 🧩

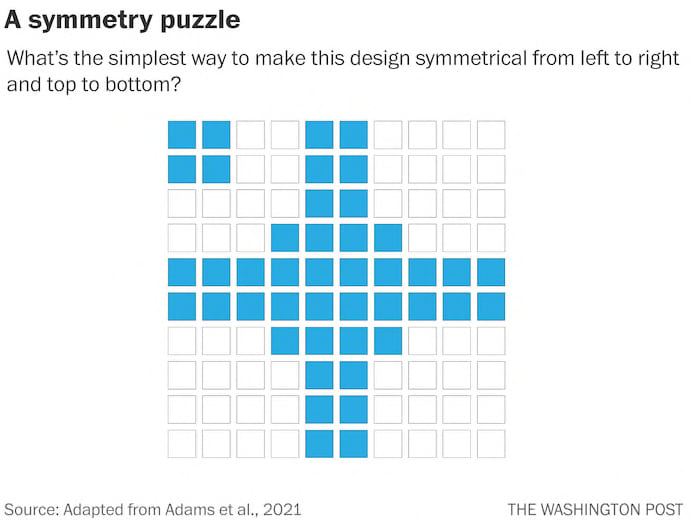

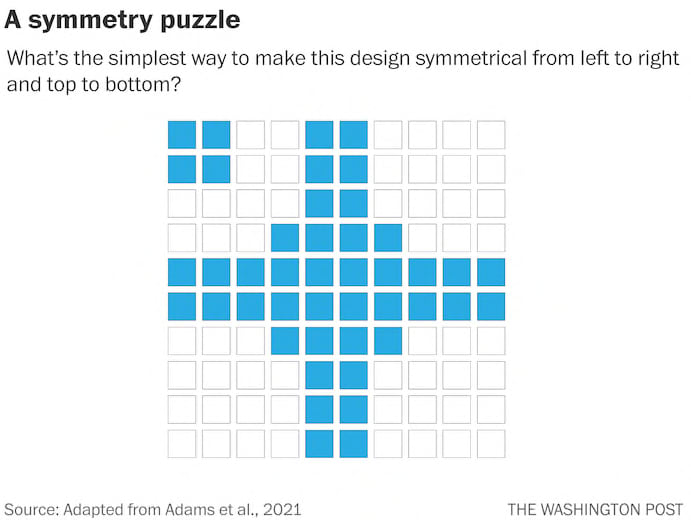

A brain teaser with an important lesson.

You’ll find no spoilers here—scroll down for the answer.

Donors and power

There’s always something happening on the money side. Or at least, a lot written about it. In fact, The Forge 🔥 (one of my favorite newsletters) ran a whole edition on philanthropy and organizing, guest edited by Democracy Alliance president Gara LaMarche.

I especially liked this piece on philanthropy and movement capture (titled “Here We Go Again”) by Megan Ming Francis (who coined the term “movement capture”) and Erica Kohl-Arenas. They recap histories of philanthropic capture—from Cesar Chavez to the NAACP’s focus on school desegregation over racial violence—and look with caution at present funding commitments. This: 👇

[A] central problem in philanthropy: many funders want to fund “movement building” but do not actually know what that entails. Deep investments in movement building would require funders to engage deeply in the history of social movements, to shift how they evaluate success, and to adopt longer time horizons. If funders want to decrease the degree of movement capture in the present moment, they must transform internal and external grantmaking processes. In particular, foundations need to look internally to foundation processes that have undermined movements; externally, funders need to do much better at trusting the vision of organizers from communities most affected by an issue.

🖥️ Webinars worth watching: The EDGE Funders Alliance ran a recent series of conversations on flipping accountability to shift power; global perspectives on funding justice and equity; and trust, relationships, and breaking power dynamics in grantmaking.

❤️ One thing I loved: the webinars had live language interpreters. That allowed presenters to speak in their preferred languages while audience members selected (using a built-in Zoom feature) to hear interpretation in several language options. More of this please.

MacKenzie Scott’s funding - Back in June, when MacKenzie Scott announced over $2.74 billion in gifts, we all noted the embrace of equity and movements, and the lack of restrictions or even reporting on the gifts. Much has been written about it, and it feels like old news already. But I’m still struck by the scale.

Just because it’s hard to wrap our heads around a big number like that, let’s do a back-of-the-envelope on this:

Assume that a new staff position averages ~$100k/year (including benefits, computer, work space, travel for their work, etc). It’ll be less in some places, but it’s a nice round number so let’s go with that.

$2.74 billion = 5,480 people working full-time for 5 years.

Across 286 recipient organizations, that’s about 19 new staff positions each—fully funded, with no restrictions, for 5 years. Imagine what that might do for most organizations.

Some folks have pointed out the lack of any plan for learning from this experience, either to inform Scott’s future giving or influence other donors’ forays into similar approaches. Grant applications and reports, the thinking goes, at least ensure some sort of feedback loop. But as a feedback loop—whether for accountability, learning, or both—where they’ve always fallen short is in being very donor-centric.

I don’t know what Scott or her advisors at Bridgespan had in mind, but the “learning plan” that I infer from the list of recipients is a more open approach, supporting sector-support and sector-change organizations like Candid, Center for Effective Philanthropy, National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, and others. So rather than a feedback loop, maybe what we’ll get is a feedback ecosystem. That would be another norm we should be grateful to see her smash.

Back to our brain teaser 🧩

Here’s our brain teaser again:

The answer: According to the researchers who used this in a study, the simplest way to make the design symmetrical is to remove the four blue squares in the upper left.

But apparently only half of people presented with this problem will find that solution. The others tend to fill in the four squares in the other corners. That is: many people add new squares rather than subtract existing ones.

The researchers’ conclusion: we tend to solve problems by adding new things, and miss solutions that involve taking something away.

(I tend to agree with the overall conclusion, which is supported by other examples, but I’d quibble on this one. I happen to think “make the whole thing blue” is also a simple solution—but I suppose the researchers define “simple” as “change the fewest squares”.)

Architects and designers sometimes express this principles as: “less is more.” I think there are organizational and social change lessons here too.

Some examples I’ve stumbled across recently:

Hans Taparia argues in SSIR that we might be better off without ESG investing.

Malaka Gharib for NPR on how less travel might mean better “voluntourism”.

And from the “what gets measured gets managed” department: researchers have developed an Organizational Bullshit Perception Scale. To be honest, I’m not 100% sure this study is real, but it’s something we could do with having less of anyway!

So next time you’re asked to brainstorm about new things you could be doing, ask instead what you could take away. Maybe even create a “stop doing” list alongside your to-do list.

Loose ends

Three little words: Tricia Wang takes down design thinking’s favorite magical phrase—“how might we”.

Rooting something out is harder when someone’s making money off it: “Disinformation for Hire, a Shadow Industry, Is Quietly Booming” (NYT)

Measuring power: in an excerpt from their book Prisms of the People, Hahrie Han, Liz McKenna and Michelle Oyakawa discuss the influence of the New Virginia Majority in exploring how to measure power.

The Sackler family has been banned from putting its name on things. 👏

Less than we bargained for? The New Humanitarian’s Jessica Alexander reviews the history and current challenges of the “Grand Bargain” (part 1 and part 2) that was meant to bring localization and participation into the humanitarian system. How’s it going after five years? 😬

A necessary challenge: Do consultants in social change perpetuate the status quo? Leah Reisman writing for the Center for Effective Philanthropy.

More will be shared on the book “soon” but how soon is contingent on project flow, coffee supply, consistently open schools, and toddler sleep schedules.